Developing a SURF-1 Gene Therapy

By Dr. Leora Fox on behalf of Cure Mito Foundation

By Dr. Leora Fox on behalf of Cure Mito Foundation

Since its inception in 2018 as the Cure SURF1 Foundation, Cure Mito has devoted significant resources to the development of a gene therapy for the treatment of SURF1 Leigh syndrome. Here we provide a plain-language description of the science behind this approach, as well as the history of its development, and current progress.

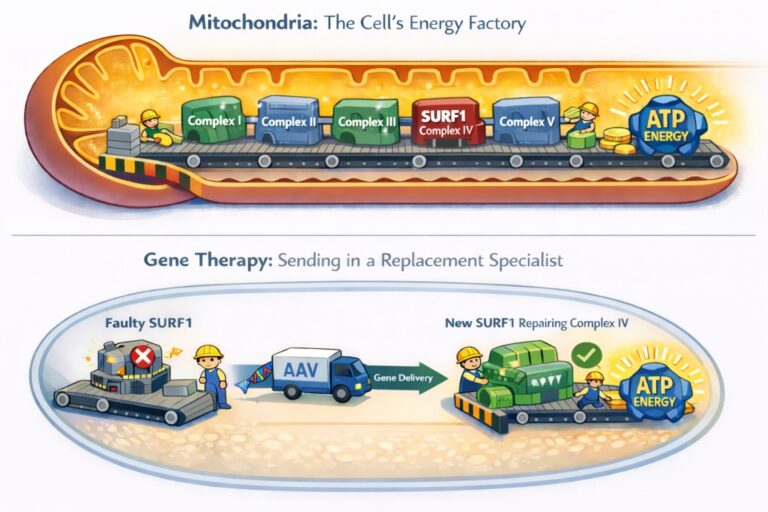

To understand the goals of SURF1 gene therapy, let’s first talk about the biology underlying Leigh syndrome. Our cells contain structures called mitochondria, sometimes known as the “powerhouses” or “batteries” of the cell. After the food we eat gets broken down into small molecules, the mitochondria combine it with oxygen to make ATP, the cell’s usable energy. The process involves several steps and a complex electron pumping system, a bit like a conveyer belt made of hundreds of protein machines. When any one of them isn’t doing its job properly, the belt jams and energy production starts to fail.

Genetic spelling changes (mutations) in more than a hundred genes can cause Leigh syndrome, but one very common source of the disease is a gene called SURF1. Within the energy-producing conveyer belt, SURF1 is the specialist that helps build and maintain the very last machine on the line – the one that works closely with oxygen. This step is critical, so if SURF1 fails at its job, the whole production gets backed up, and there’s less energy available. This especially weighs on the brain and spinal cord, which can explain many of the neurological, movement, and sensory symptoms of Leigh syndrome. An effective SURF1 gene therapy would be like sending in a replacement specialist to work on a critical machine on the conveyer belt, ultimately restoring energy production.

To achieve this, scientists package a healthy version of the SURF1 gene, without spelling mistakes, into a harmless genetic delivery system known as an AAV. An AAV is a modified virus that cannot cause disease and is used only as a vehicle – like a biological delivery truck – to carry genes into cells. AAVs are usually injected spinally, into the fluid that bathes the nervous system. This allows the SURF1 gene to enter many cells, riding in the AAV. After just one treatment, the cell starts making the functional protein. This is like bringing in a technician who can get things moving again.

The history of developing a SURF1 gene therapy is linked closely with the history of our Foundation. In 2018, families whose young children had been diagnosed with SURF1 Leigh syndrome formed the Cure SURF1 Foundation. We led a grassroots fundraising effort and partnered with the University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center, which houses many experts in genetic therapies for rare neurological disorders. Cure Mito funded research scientist Dr. Steven Gray and his team, providing upwards of $1 million to develop a SURF1 gene therapy that could be delivered with an AAV, in hopes of replacing the faulty machinery, just as described above.

Dr. Gray’s team designed and generated the SURF1-AAV gene therapy. They tested it in human cells grown in dishes, where it seemed to restore the activity of some of the machinery driving energy production. These human cell models, known as fibroblasts, were developed from skin biopsies donated by Leigh syndrome patients from around the world, an effort that was organized by Cure Mito.

A member of Gray’s team, Dr. Qinglan Ling, spearheaded animal experiments, delivering the SURF1 AAV gene therapy to laboratory mice that were missing the SURF1 gene (SURF1 knockouts). These mice are useful for studying Leigh syndrome and possible treatments, because they show many of the same basic problems, including missing parts and less energy production along the “conveyer belt.”

SURF1 knockouts reproduce some of the features of Leigh syndrome, such as muscle weakness and premature death. Notably, they don’t have the brain and nerve damage that is seen in people, nor the loss of developmental milestones or severity of symptoms. No model is perfect, but many can be useful for studying certain aspects of disease.

Ling and colleagues delivered the one-dose SURF1 AAV therapy to the SURF1 knockout mice, then closely studied their tissues, publishing a paper in 2021. They observed many benefits to the energy production machinery within mitochondria, confirming that the new SURF-1 could restore some of the energy production.

This promising data attracted the interest of the biotechnology company Taysha Gene Therapies, which aimed to advance the program toward a human clinical trial. To initiate a clinical trial, researchers must prepare and submit an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the FDA for review and approval. There are also special pathways for drugs intended to treat rare disease, and through Taysha’s efforts, the SURF-1 AAV drug received Orphan Drug Designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2020. This status helps to speed and lower the cost of developing drugs for rare diseases.

Dr. Gray’s laboratory continued to work on the therapy; as a next step they tested it in larger animals: healthy, or “wild type” rats. This step is often required to ensure safety. Unfortunately, their original SURF1-AAV design did not seem to be safe enough to try in humans. These findings, along with financial constraints, prevented Taysha from moving forward with that clinical trial.

Meanwhile, Cure SURF1 was expanding its efforts to include other causes of Leigh syndrome and mitochondrial disease, and rebranded as the Cure Mito Foundation in 2021. We continued to support Dr. Steven Gray’s work, and along with additional funding secured from the RTW foundation in 2023, his team proceeded to refine their approach. This led to the development of a new and improved SURF1 AAV. They have tested it carefully in human cells, SURF1 knockout mice, and wildtype rats. Gray’s team found their redesigned SURF1-AAV to be similarly effective (and safer) than the original, publishing the newest results in August of 2025.

In parallel, the Gray lab generated a “knockout” rat that is missing the SURF1 gene, which they are studying closely to understand how it mirrors human disease – a process known as characterizing the animal model. Around 2023, they began early studies to explore the SURF1 gene therapy in this rat model, with joint funding from Cure Mito and RTW foundation.

The next goal is to take steps towards a clinical trial in humans. To this end, in early 2025 the team at UT Southwestern organized what’s known as a pre-IND meeting with the FDA. This is a way to make sure that the researchers are aligned with regulators about how they plan to study a potential treatment or Investigational New Drug (IND). In this meeting, they received guidance on a basic plan to develop their improved SURF1 gene therapy. They discussed how they’ll produce and test it further in animals (rats) – and ultimately in people with Leigh syndrome.

Importantly, that meeting helped the scientists to draw a road map for reaching a clinical trial, which includes (1) switching to the improved AAV, (2) finding a manufacturer and making enough drug for animal testing, (3) doing larger, careful experiments to confirm the safety of the new SURF1 treatment in wildtype rats, (4) manufacturing more drug in a specialized way that makes it suitable for human testing, (5) submitting an official IND application to the FDA, and finally (6) designing a clinical trial.

During Cure Mito’s annual virtual symposium in September 2025, Dr. Gray explained that they were currently working towards identifying a drug manufacturer. The process of designing, testing, and running human trials on a novel rare disease therapy can cost millions of dollars, which is why the fundraising efforts of community organizations like Cure Mito are so important.

In the space of a few years Cure Mito has supported development of a SURF1 gene therapy, as well as new models to test its effectiveness. In 2023, Cure Mito provided $106,000 in funding, alongside $150,000 from the RTW Foundation, to support early studies using a newly developed SURF1 knockout rat model and to begin exploratory evaluation of the SURF1 gene therapy in this system. In 2025, Cure Mito awarded an additional $203,000 to continue studying the SURF1 rats and to conduct additional testing in SURF1 mice of the new and improved SURF1 AAV. In total, since 2018 Cure Mito has funded over $1.5 million towards the development of a SURF1 gene therapy.

There is a clear path forward for the newest iteration to be tested in humans in the future, but this will require perseverance and additional funding. Manufacturing, animal testing, designing a clinical trial, and submitting an IND are estimated to require approximately $2,870,000.

Despite setbacks, there has been continuous and active progress towards the development of a SURF1 gene therapy for the treatment of Leigh syndrome. Another positive outcome is that Dr. Qinglan Ling, originally a postdoc in Dr. Gray’s lab, obtained a position as Assistant Professor at UMass Chan Medical School, Department of Genetic and Cellular Medicine, where she now runs her own lab studying Leigh syndrome and training future scientists.

Meaningful progress requires investing not only in strong science, but in the people who will advance the field over time. Furthermore, both the SURF1 science and the lessons learned about the process of translating discoveries into medicines will inform the development of gene therapies for other causes of Leigh syndrome.

This 2021 blog post from Coriell, the company that created and now houses patient fibroblasts, describes Cure Mito’s skin sample collection efforts.

This work from 2003 characterized mice that were missing the SURF1 gene and described the ways they reproduce symptoms and the ways they do not.

This 2021 paper demonstrated that the original SURF1 gene therapy could improve some of the features of Leigh syndrome.

This 2025 publication showed that the new SURF1 gene therapy design was safer in both mice and rats.

Your donation to The Cure Mito Foundation supports life-changing research, connects families to critical resources, and brings hope to those living with Leigh syndrome and mitochondrial diseases.