When Rosário talks about her son, Gonçalo, she does not begin with a diagnosis. She begins with how their family came together. “Our history is not a very common one, because my son is an adopted child.” Gonçalo came to their family from another country when he was almost two years old. At the time, they knew very little. They were told he had been born prematurely, though no one could say by how many weeks. They knew his biological mother had health issues that, much later, they would come to understand were likely connected to mitochondrial disease. But Gonçalo himself seemed healthy. He was small, yes, and there were some developmental differences, but nothing that suggested the path their lives would take. “He was developing very well when we met him… He adapted just fine.”

As Gonçalo grew, small challenges began to surface. Coordination was difficult. Writing and drawing took more effort. Riding a bike required patience and time. Still, he progressed, learned, and found his way forward. To Rosário, he was simply her child: tiny, determined, and, in her words, adorable.

When primary school began, things became more difficult. Learning to read and write did not come easily, and math was overwhelming. Doctors ordered tests. An MRI revealed lesions in his brain, but bloodwork came back normal. For years, they believed the explanation lay in a lack of oxygen during his difficult birth.

Then, when Gonçalo was nine years old, everything changed.

Another MRI showed new lesions. This time, they could not be explained away. A doctor immediately raised the possibility of Leigh syndrome. Genetic testing followed, this time focused on mitochondrial DNA. “And some months later, we had results, and it was Leigh, but it is not…the common type of Leigh.” Gonçalo had a mutation typically associated with LHON, Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy, combined with a nuclear DNA mutation that caused Leigh syndrome. Until then, he had not experienced epilepsy or major crises. His challenges were developmental, physical, and gradual.

Then came February 2023.

“And then exactly at the same time as the diagnosis, he had his first crisis. He was very tired… and one day he woke up and his left arm was not normal, it was up. It was terrible.” That week, they went back and forth to the hospital several times. Doctors were careful, trying to keep him from unnecessary exposure to viruses. He began a mitochondrial cocktail. “This was in February 2023, and he didn’t have another crisis after that.”

Today, Gonçalo takes CoQ10, riboflavin, and B vitamins. The change has been meaningful. “He reacted very well to that.” He is twelve now, nearly thirteen. He has weakness on his left side, with lesions affecting the right side of his brain. His arm rests differently than other children’s do, his gait tires easily, but his body still carries him where he wants to go.

“So if he wants to climb a tree, he is able to climb the tree… The doctor was amazed, because he’s really fine.” Rosário is careful not to paint an unrealistic picture. Leigh syndrome is still there, and so is uncertainty. But most importantly, so is Gonçalo. “I think it’s also important to know these atypical cases, because, after all, they give us hope,” Rosário notes.

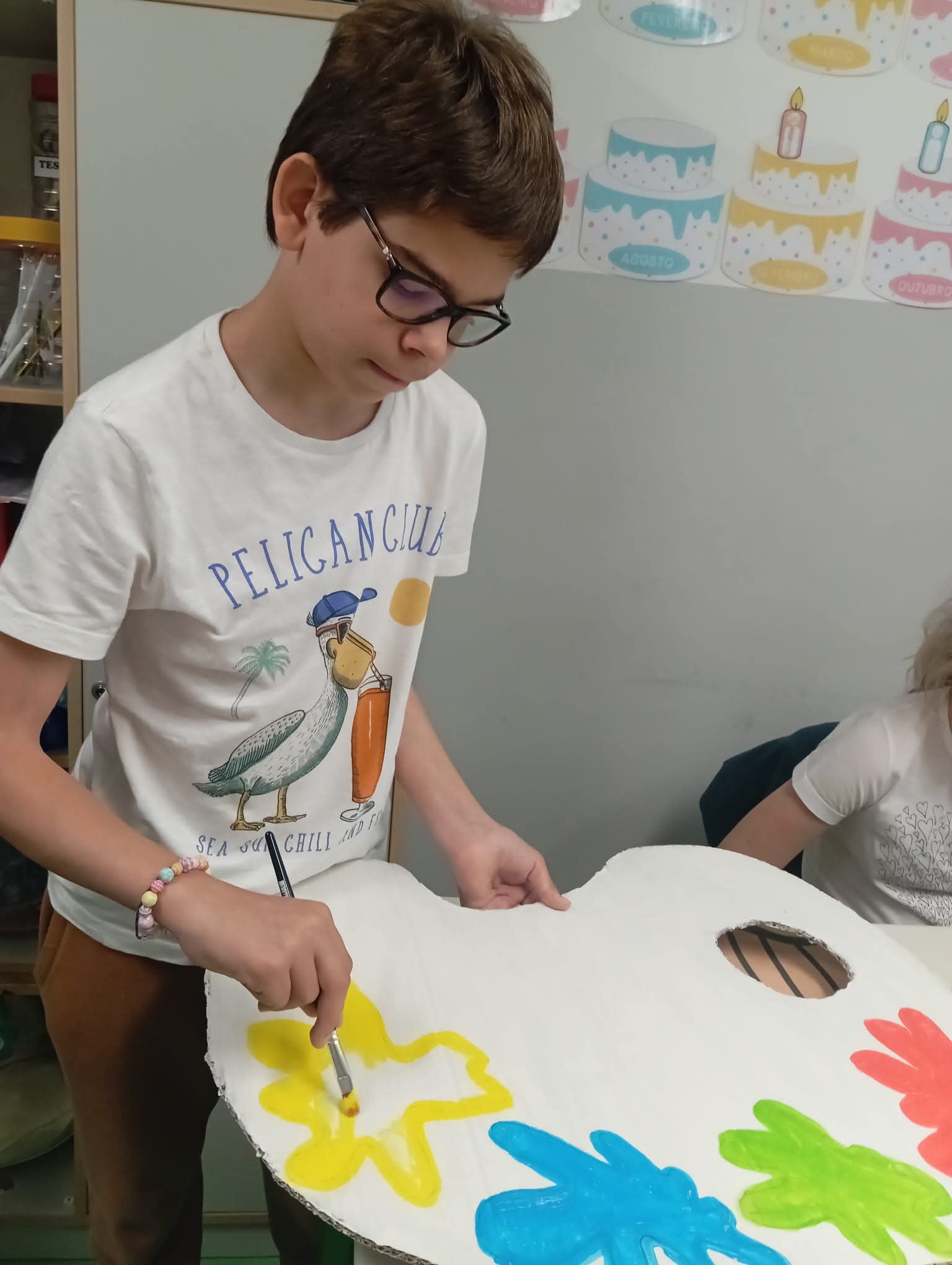

School continued to be a struggle for Gonçalo. In a traditional classroom, there was bullying and he felt different. Now he attends a specialized school, where there’s a sense of belonging. “He doesn’t feel different anymore,” Rosário explains. Gonçalo may read slowly, but he reads. He writes in capital letters, but he writes. One day, he came home feeling proud, holding a recipe he had written himself. They used the recipe to bake biscuits together.

“And he’s a very happy boy,” Rosário shares, with pride. After the diagnosis, Rosário and her husband made a thoughtful change to their daily routine. “When we heard about… the prognosis not being a happy one, we decided that he would be a happy child.” Every night, before bed, they make sure Gonçalo feels calm, loved, and safe. “It’s [been] almost three years now, and… we didn’t fail.”

Rosário has made other intentional choices that have reshaped her life. She is a university professor of medieval history, teaching at the oldest university in Portugal. After Gonçalo’s diagnosis, she stepped away from her work. “So I’m completely dedicated to him now,” she says. She takes him to therapies, watches him swim, and cheers for him in the water, where he feels free and strong. “I call him my little fish.”

Their family vacations are filled with stories read aloud, drawing, painting, and of course, swimming at the beach. Harry Potter, reptiles, and being held are just a few of the things that bring Gonçalo joy. He loves fiercely and openly. “He’s a very, very lovable boy. He’s very sweet. He loves to embrace,” his mom shares sweetly.

When asked what she would tell newly diagnosed families, Rosário’s answer is honest and hard-earned. “[Try not to] think too much about all the awful things that can happen, because other things can happen too.” She emphasizes the importance of research, community, and finding Cure Mito across the Atlantic and feeling less alone. “First of all… we are not alone. Yeah, that’s the first thing, and it’s so, so important.”

There’s a chance Gonçalo will lose his vision one day. Rosário is painfully aware of this possibility, yet she prepares without surrendering joy. “Of course I look happy,” she says. “My son is well, so I look happy, and I need to look happy for him, too.” Rosário chooses to read another chapter with Gonçalo tonight. To swim another hour tomorrow. To make a recipe he wrote in careful letters. To stay present inside the life that is here, right now. “It’s possible to live day by day and not think about two years [in the future],” she insists. Afterall, it’s the only way to avoid missing out.

Gonçalo is not a statistic. He is a boy who brought his mother a lollipop (and both of us pure joy) during our video interview. He is a child who loves the water, stories, and being close to the people who love him. His story matters not because it’s rare, but because it’s real. It reminds us of the only thing that is truly guaranteed: this very moment.